by Dianna Brodine, managing editor, PostPress

While the stories about attempts to initiate fraudulent wire transfers have been circulating for a while now, a recent warning from the FBI brought additional attention to the problem. At the same time, a manufacturer in Erie, Pennsylvania, was the target of an attempt.

While the stories about attempts to initiate fraudulent wire transfers have been circulating for a while now, a recent warning from the FBI brought additional attention to the problem. At the same time, a manufacturer in Erie, Pennsylvania, was the target of an attempt.

Fraudulent wire transfer request attempts on the rise

On May 4, 2017, the Federal Bureau of Investigation issued Public Service Announcement Alert Number I-050417-PSA to warn of an increase in the number of wire transfer fraud attempts. According to the alert, a 2,370 percent increase in identified exposed losses occurred between January 2015 and December 2016. The scam has reached all 50 US states and more than 130 countries. The alert provided the following explanation of the fraud and its intended victims:

Business Email Compromise (BEC) is defined as a sophisticated scam targeting businesses working with foreign suppliers and/or businesses that regularly perform wire transfer payments. The Email Account Compromise (EAC) component of BEC targets individuals that perform wire transfer payments.

The scam is carried out when a subject compromises legitimate business email accounts through social engineering or computer intrusion techniques to conduct unauthorized transfers of funds.

The victims of the BEC/EAC scam range from small businesses to large corporations. The victims continue to deal in a wide variety of goods and services, indicating that no specific sector is targeted more than another.

It is largely unknown how victims are selected; however, the subjects monitor and study their selected victims using social engineering techniques prior to initiating the BEC scam. The subjects are able to accurately identify the individuals and protocols necessary to perform wire transfers within a specific business environment.

The FBI’s collected data indicate banks in China, Hong Kong and the United Kingdom are the primary depositories for wire transfer fund requests. In the six months spanning June 2016 and December 2016, more than 3,000 US businesses were targeted, with an exposed dollar loss of nearly $350 million.

A manufacturer’s experience

Thanks to an alert employee and some informal training and internal procedures, a small Pennsylvania manufacturing firm avoided adding its names to the list of scammed businesses.

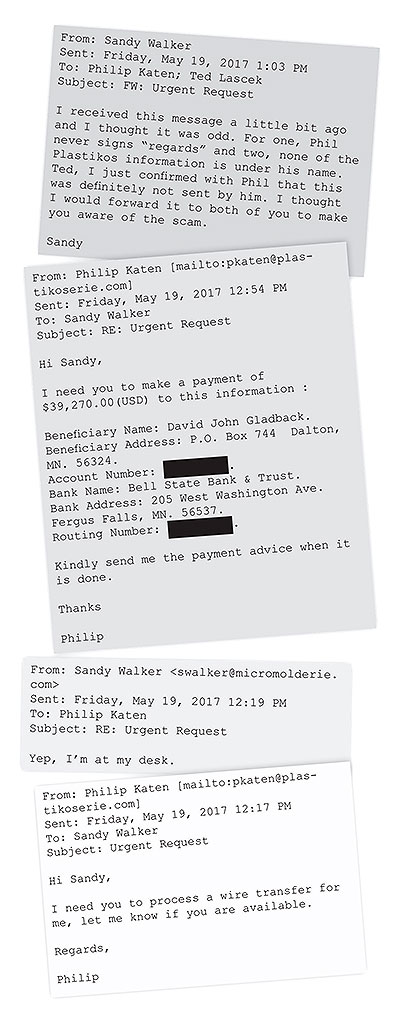

On May 19, an email was sent from Plastikos President Philip Katen to employee Sandy Walker with an urgent request for a wire transfer. The email asked if she was available and, when she replied in the affirmative, a second email arrived with wire transfer details. While the first email didn’t immediately raise any red flags, the second email made Walker pause.

“Nine out of 10 Fridays, I go over accounts payable in the afternoon,” explained Katen. “On the day the emails came through, I arrived and – coincidentally – that second email came within few minutes of when I walked in. I walked past Sandy to my desk, which is literally next door to hers.” When Walker saw Katen arrive, she wondered why he hadn’t stopped at her office if the request was truly urgent.

“A few minutes later,” Katen explained, “she came in to ask a question about the wire transfer – which obviously generated confusion. I looked at her with a ‘what are you talking about’ expression. Immediately, she knew something was not right.”

A few minor points tipped Walker off. First, the initial email contained very little information and was signed “Regards, Philip,” which is different than the language Katen would typically use. Second, although Katen might request a wire transfer initially via email, the company’s standard protocol calls for him to then call or visit her in person to discuss the process as a sort of verbal review and confirmation. “She was expecting those procedures to kick in,” he said, “and when they didn’t, it raised her suspicions further.”

The the company’s staff members weren’t completely unaware of the prevalence of internet fraud attempts. Katen had heard other companies discussing their own experiences at conferences and local Erie, Pennsylvania, manufacturer educational outreach efforts. As a result, he had shared the information with the accounting and IT departments during regularly scheduled team meetings. “It was an informal, continuing educational opportunity,” he said, “and something we shared at a time when we might also share cybersecurity updates from our bank. Luckily, those conversations planted a seed that saved us a significant amount of money in this instance.”

Katen called the FBI to report the attempt, and the responding agent stressed that awareness is the best tool to prevent these scams. “He encouraged us to keep people informed, educate them on the possibilities and come up with formal policies and procedures to bolster that defense,” said Katen. “Nothing can replace the human recognition/awareness component, however. And, that’s the first thing that kicked in here.”

Awareness is the first defense

Based on the company’s experiences, the company formalized some of the internal controls that had been a guideline, rather than the rule. Katen also took advantage of the educational opportunity to share the experience with other company employees.

“We printed off the emails and passed them around to the other department staff members,” he explained. “Although some felt it was a little strange when they initially read the emails, they all were shocked when we told them it was a fake request. We talked about what happened, reinforced that the internal protocols had worked and shared that the crisis had been averted. But, it was a good way to bring that awareness to the forefront for everyone on our team.”

In addition, a strict procedural outline was developed that includes a phone call to an authorized company executive to confirm the request as the first step. “If we legitimately have requested a funds transfer, we should be readily available to talk with our staff and discuss what’s needed,” said Katen. “If not, that’s the first indicator that something definitely isn’t right.”

Additional protocols are in place related to bank accounts and security authorizations – limits and restrictions intended to force checks and balances.

Lessons learned

Katen offered advice based on the his company’s experience and information shared by an FBI agent. The FBI agent encouraged companies to train their staffs to be aware of potential areas in which information is shared. Criminals are monitoring social media sites, reviewing company websites, reading industry articles and even potentially hacking into servers to read company emails in order to research names and titles of those responsible for financial transactions, all in an effort to make their wire transfer request emails appear more realistic.

The agent also told Katen that the vast majority of cyberattacks are state-sponsored events originating primarily in China, Russia and North Korea. Some of these attempts are run as military operations and, Katen was told, the US does not have the resources to effectively combat the threat. “The notion that the FBI or whomever else would be able to serve as a line of defense is not realistic because of the sheer volume of people on the other side who are employed to do this,” Katen explained.

In most cases, while all victims of the scam are asked to contact the FBI to help prevent future incidents, there is little that can be done if money is wired outside the US. Katen was told the money often is routed through countries that are not US allies, so the likelihood of retrieving any lost funds is virtually zero.

“We heeded the warning when we heard about it happening to other plastics processing companies, and we incorporated internal accounting procedures and controls as recommended when an FBI agent spoke to our local manufacturing industry group,” Katen continued.

The message to others is simple. “By and large, you’re largely responsible for yourself,” he said. “Come up with procedures to protect your company. Recognition and awareness are the best – and in many cases, the only – lines of defense.”

Suggestions for Protection

- The FBI’s Public Service Announcement Alert offered a list of self-protection strategies. A few are listed here, but readers are encouraged to visit www.ic3.gov/media/2017/170504.aspx to view the entire list.

- Avoid free web-based email accounts: Establish a company domain name and use it to establish company email accounts in lieu of free, web-based accounts.

- Be careful what you post to social media and company websites, especially job duties and descriptions, hierarchal information and out-of-office details.

- Consider additional IT and financial security procedures, including the implementation of a two-step verification process. For example:

- Out-of-Band Communication: Establish other communication channels, such as telephone calls, to verify significant transactions. Arrange this two-factor authentication early in the relationship and outside the email environment to avoid interception by a hacker.

- Digital Signatures: Both entities on each side of a transaction should utilize digital signatures. This will not work with web-based email accounts. Additionally, some countries ban or limit the use of encryption.

- Do not use the Reply option to respond to any business emails. Instead, use the Forward option and either type in the correct email address or select it from the email address book to ensure the intended recipient’s correct email address is used.

- Consider implementing two-factor authentication for corporate email accounts. Two-factor authentication mitigates the threat of a subject gaining access to an employee’s email account through a compromised password by requiring two pieces of information to log in: (1) something you know (a password) and (2) something you have (such as a dynamic PIN or code).

- Register all company domains that are slightly different than the actual company domain.

- Confirm requests for transfers of funds. When using phone verification as part of two-factor authentication, use previously known numbers, not the numbers provided in the email request.

- Carefully scrutinize all email requests for transfers of funds to determine if the requests are out of the ordinary.