By Chris Kuehl, managing director

Armada Corporate Intelligence

Just like seeing Santa setting up at the local mall in August, it is never too soon for an economist to start looking at the coming year – as if the changing of a calendar has any real bearing on economic performance. The truth is that most of the issues that will vex and concern next year are the issues that are vexing and concerning now. The challenge is determining which of these are likely to fade from view and which will continue to build in significance. The four concerns that seem destined to shape the majority of the economic conversations in the coming year include 1) the ongoing trade and tariff war between the US and China, as well as other nations; 2) the potential for a recession in the US; 3) the ongoing crisis in terms of workforce development; and 4) the influence of politics on the overall mood of the consumer and how that affects the economy.

Factor 1: Trade and tariffs

The trade and tariff war between the US and China has transcended its origins and metamorphosed into a much more comprehensive confrontation that will determine how the US and China will coexist in the future. What started as a relatively simple demand that China reduce the trade deficit the US runs by buying more from the US has become a battle of economic systems. The US now demands that China stop subsidizing its business community, cease attempting to steal US technology, end its currency policy, stop oppressing the Uighur and Tibetan communities, accede to the demands of the Hong Kong protestors, leave Taiwan alone, withdraw from the South China Sea, etc. The list goes on and on. From the 1950s to the ’80s, the US considered China an enemy, but in the ’90s, that started to change, and China became a trade partner – as well as an economic rival. That shift has not worked out as well for the US as hoped, and there now is a move to return to more of a Cold War relationship. It is significant that none of the Democratic candidates are assailing Trump for his hostility toward China – they only object to his methods. The trade war will continue throughout the next year, with ups and downs as both sides experiment with agreements and truces.

The trade and tariff war between the US and China has transcended its origins and metamorphosed into a much more comprehensive confrontation that will determine how the US and China will coexist in the future. What started as a relatively simple demand that China reduce the trade deficit the US runs by buying more from the US has become a battle of economic systems. The US now demands that China stop subsidizing its business community, cease attempting to steal US technology, end its currency policy, stop oppressing the Uighur and Tibetan communities, accede to the demands of the Hong Kong protestors, leave Taiwan alone, withdraw from the South China Sea, etc. The list goes on and on. From the 1950s to the ’80s, the US considered China an enemy, but in the ’90s, that started to change, and China became a trade partner – as well as an economic rival. That shift has not worked out as well for the US as hoped, and there now is a move to return to more of a Cold War relationship. It is significant that none of the Democratic candidates are assailing Trump for his hostility toward China – they only object to his methods. The trade war will continue throughout the next year, with ups and downs as both sides experiment with agreements and truces.

It is not just the US contest with China that will affect trade. The US is rethinking its entire role in the global trading system, as much of that policy has been rooted in reaction to previous wars. The US granted extraordinary access to its market to help Europe recover at the end of the World War II, and this access remains in place. During the Cold War, nations received trade access to the US in return for supporting the US position against the Soviet Union. Even though the USSR ceased to exist in 1989, these trade agreements remain in place. The US now is examining all of these deals through a much more nationalistic lens, and the goal clearly is to shift more activity back to the US. With this come the threats of slower global growth and more expensive consumer goods. The trade-offs will come under intense scrutiny in the years to come.

Factor 2: Recession potential

The second major issue to play out will be the potential for a recession in the next 12 to 24 months. There are arguments to be made for an imminent recession and arguments suggesting that the worst-case scenario will be a slowdown that takes annual growth to between 1.5% and 2.0%. The current data show a developing weakness in the manufacturing sector with contraction readings from the Purchasing Managers’ Index, reductions in capacity utilization, slowing demand for durable goods and consistent reports suggesting manufacturers have become cautious. It has been pointed out that the yield curve has been inverted for an extended period of time and, in the past, this has pointed to a recession in the next 12 to 24 months. The global economy has not been this slow in decades, and estimates of its health continue to weaken every month. Germany already is in recession, and much of Europe is not far behind. It is indeed worrisome.

The second major issue to play out will be the potential for a recession in the next 12 to 24 months. There are arguments to be made for an imminent recession and arguments suggesting that the worst-case scenario will be a slowdown that takes annual growth to between 1.5% and 2.0%. The current data show a developing weakness in the manufacturing sector with contraction readings from the Purchasing Managers’ Index, reductions in capacity utilization, slowing demand for durable goods and consistent reports suggesting manufacturers have become cautious. It has been pointed out that the yield curve has been inverted for an extended period of time and, in the past, this has pointed to a recession in the next 12 to 24 months. The global economy has not been this slow in decades, and estimates of its health continue to weaken every month. Germany already is in recession, and much of Europe is not far behind. It is indeed worrisome.

At the same time, encouraging signs have suggested the expansion still has some life left in it. Recovery from the recession in 2008 has been very slow, but that has been a bit of an advantage as it often is the rapid rebound from a downturn that sets up the next downturn. The fast recovery usually brings inflation and provokes the Federal Reserve to intervene with higher rates. Inflation also slows bank lending. This time around, there has been little inflation to contend with – as a matter of fact, there has been more concern regarding deflation.

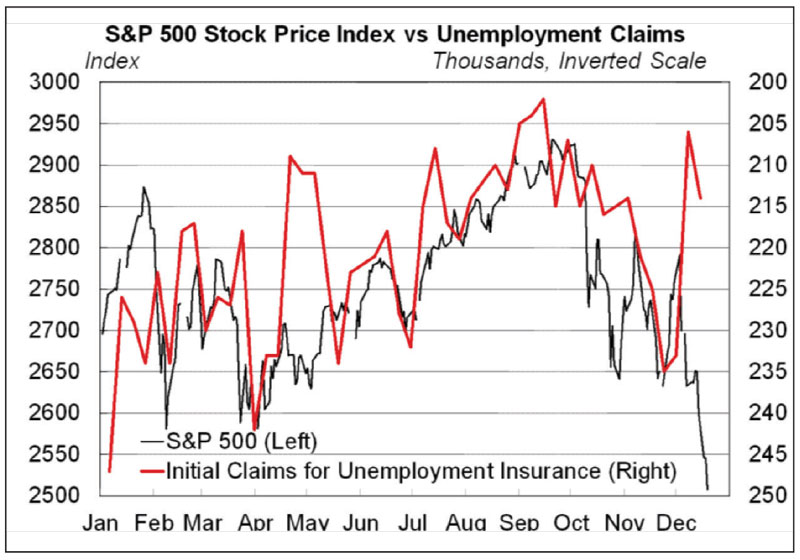

There will be three crucial indicators to watch as far as an impending recession is concerned. The first would be any sign of a deteriorating employment situation. If there are mass layoffs and the jobless rate starts to climb, there will be an immediate impact on the consumer’s attitude – even if the overall rate stays traditionally low. A rate of 6.0% unemployment still is considered normal, but if the jobless numbers go from 3.5% to 6.0% there will be real panic. The second thing to watch is consumer confidence and its impact on retail sales. Consumers can shift attitude very quickly if they feel spooked by something and, if that translates into a sharp reduction in retail activity, the economy will feel it. The third area will be inflation. Thus far, the Federal Reserve has not had to worry about inflation and instead has been able to focus exclusively on stimulus. A sharp hike in commodity prices (such as oil or food) will make the Fed nervous, and there always exists the possibility that wages will start to rise. The Phillips curve holds that this should have happened by now, but for a variety of reasons this reaction has been delayed.

Factor 3: Workforce

Crisis number three is workforce related, and it is not a new problem. There simply are not enough people with the appropriate skills to fill the jobs available. In manufacturing alone there is a need for 3.7 million new workers in the next three to five years, and the estimate is that the sector will be short by more than 2 million. There is a shortage of truck drivers – 80,000 are needed right now, and it is estimated that future need will top 180,000. Too few construction workers and healthcare workers also are a problem, and now the professional positions are not being filled. Part of the issue is that Baby Boomers are retiring at a rate of 10,000 a day, and part of the issue is that too few are being trained and educated appropriately.

Crisis number three is workforce related, and it is not a new problem. There simply are not enough people with the appropriate skills to fill the jobs available. In manufacturing alone there is a need for 3.7 million new workers in the next three to five years, and the estimate is that the sector will be short by more than 2 million. There is a shortage of truck drivers – 80,000 are needed right now, and it is estimated that future need will top 180,000. Too few construction workers and healthcare workers also are a problem, and now the professional positions are not being filled. Part of the issue is that Baby Boomers are retiring at a rate of 10,000 a day, and part of the issue is that too few are being trained and educated appropriately.

In the short term, not many options present themselves as far as acquiring the needed workforce. Option one is extending people’s working lives, and that has been taking place as fewer people retire when they would be expected to. The problem is that staying on the job in one’s 60s and 70s is hard, given everything from retirement rules to age discrimination. There are efforts to retrain, but this is expensive, and there has been little help from the federal government. Instead, states and cities have shouldered this responsibility. Immigration has long been the most common option, but the people that are coming to the US now (legally and illegally) are not generally skilled, and it is the skilled worker the US needs.

Factor 4: Politics

Finally, there is the impact of a political year. Elections tend to depress voters/consumers for a variety of reasons. The first issue is that campaigns invariably focus on problems. The litany of woes is relentless, and the candidate implores the voter to pick them, as only they can rescue the country from certain destruction. The voter hears nothing but gloom and doom and begins to believe that nothing can be done. In the end, there will be many disappointed voters, as they will not be on the winning side. This year promises to be more contentious and intense than in previous years, as emotions will run very high. People are very deeply invested in either liking or disliking the candidates on offer, and this will affect mood profoundly.

Finally, there is the impact of a political year. Elections tend to depress voters/consumers for a variety of reasons. The first issue is that campaigns invariably focus on problems. The litany of woes is relentless, and the candidate implores the voter to pick them, as only they can rescue the country from certain destruction. The voter hears nothing but gloom and doom and begins to believe that nothing can be done. In the end, there will be many disappointed voters, as they will not be on the winning side. This year promises to be more contentious and intense than in previous years, as emotions will run very high. People are very deeply invested in either liking or disliking the candidates on offer, and this will affect mood profoundly.

To make matters a little worse, the fact is that politics will take over the attention of the politicians, leaving them little time to address any of the issues outlined above – resulting in lackluster policy activity on trade, infrastructure, workforce or anything else. It will be political infighting every day of the week.

These are not the only issues that will affect the 2020 economy. As always, there will be unexpected developments involving wars and natural disasters in addition to ongoing issues, such as health care, education, climate change, technology and so on. Any one of these can (and will) suddenly lurch into prominence, but the four outlined above can be counted upon to be factors all year – just as they have been factors in past years.

Chris Kuehl is managing director of Armada Corporate Intelligence. Founded by Keith Prather and Chris Kuehl in January 2001, Armada began as a competitive intelligence firm, grounded in the discipline of gathering, analyzing and disseminating intelligence. Today, Armada executives function as trusted strategic advisers to business executives, merging fundamental roots in corporate intelligence gathering, economic forecasting and strategy development. Armada focuses on the market forces bearing down on organizations. For more information, visit www.armada-intel.com.