By Liz Stevens, writer, PostPress

Holograms, those magical images that allow the viewer to see an image in three dimensions, have advanced from being rare, mesmerizing novelty items to offering practical applications and aesthetic touches on items and packaging everywhere. Unlike the earliest holograms that were produced as one-off laboratory specimens by optical scientists, today’s holograms can be manually produced via the traditional way – with lasers and mirrors and physical objects – or designed and digitally produced with nothing more than a computer and algorithms. Mass reproduction of holograms now is commonplace.

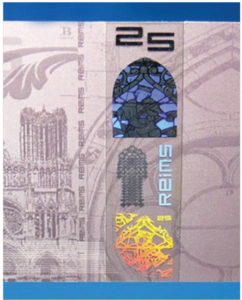

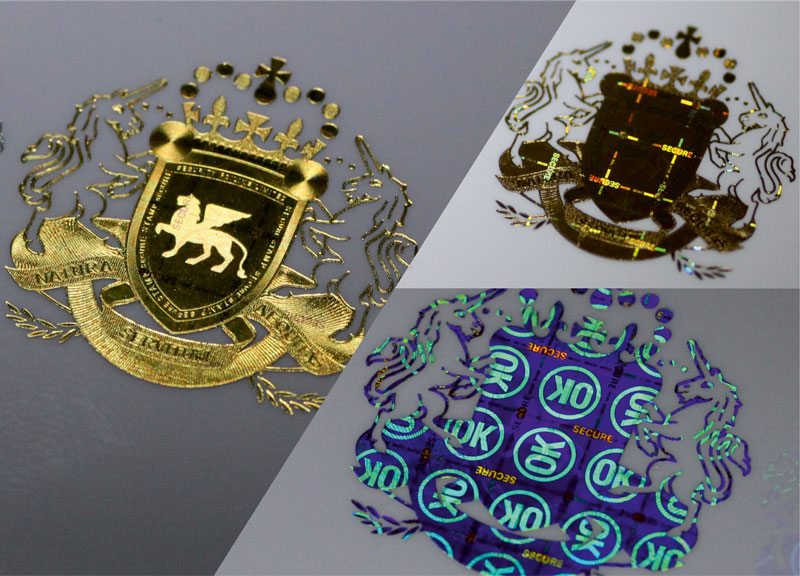

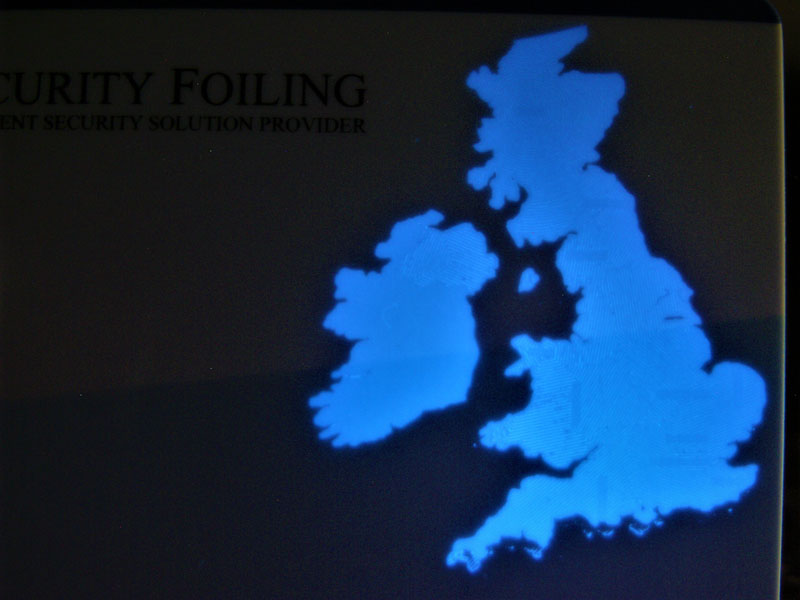

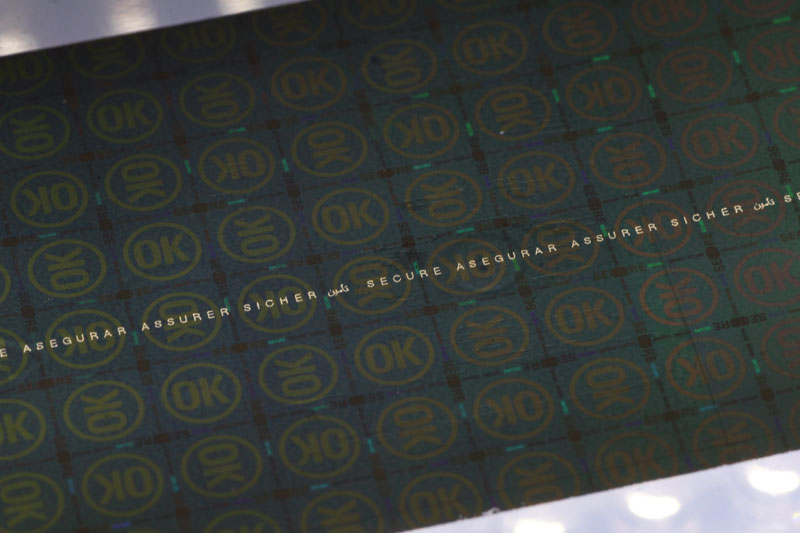

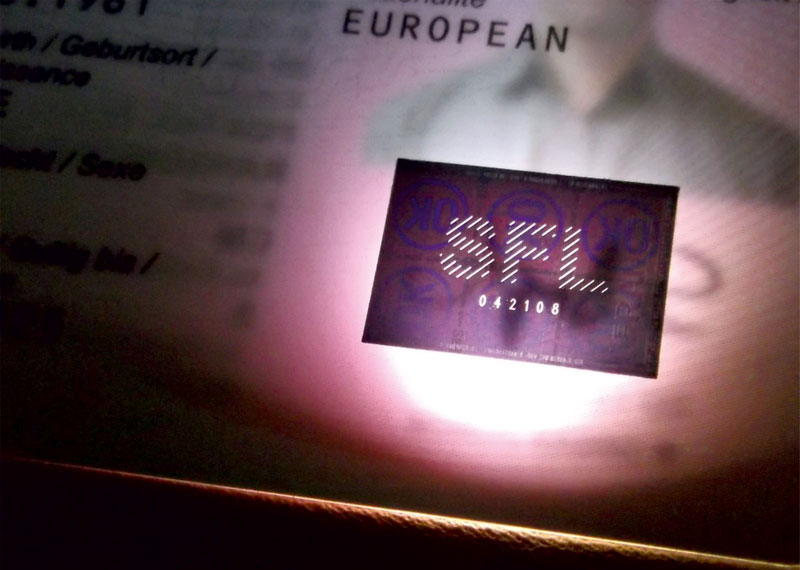

The eye-catching depth, color and beauty of holograms are put to use for a variety of purposes. They are used to authenticate product brands, to embellish packaging for high-end products and to create a tamper-proof packaging seal. Holograms are embedded in paper currency to thwart counterfeiting, affixed on identification cards and badges, reproduced on valuable documents as authentication and even stamped onto some metal coins. Event tickets, commemorative items and collectables feature dazzling holograms to reinforce their premium value. Other esoteric uses for holograms include data storage and interferometry.

Back in the Day

Credit physicist Dennis Gabor for inventing holography in 1948. The Hungarian-British scientist actually was aiming to improve that era’s electron microscopes; his unexpected invention of holography was patented and it earned Gabor a Nobel Prize in Physics. In the 1960s, laser holography was developed, eliminating the need for electron beam. Rainbow holograms soon were invented, allowing holograms to be viewed with natural light. White light holography and reflection holography came along soon after, advancing the science for displaying holograms. The emergence of dichromated gelatin – as a holographic recording medium to replace glass plates – was a development that allowed for recording holograms on any clear, non-porous surface.

A Crucial Development – Mass Print Production of Holograms

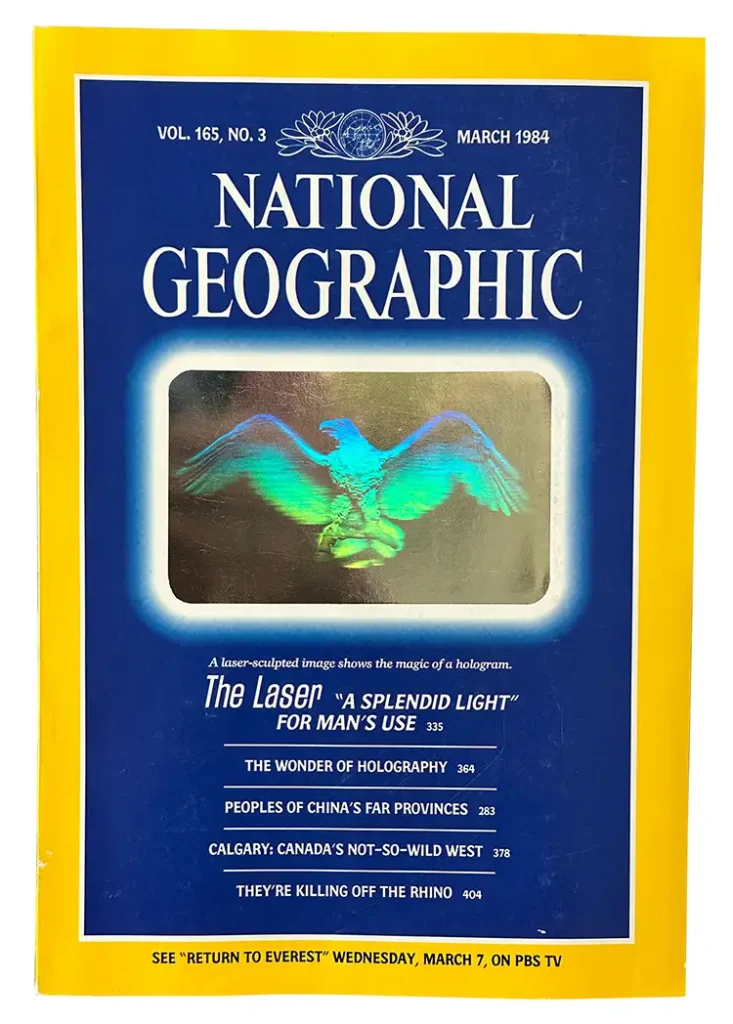

National Geographic magazine was one of the earliest publications to mass produce holograms. The magazine’s March 1984 cover featured the hologram of a bald eagle. Each copy of the magazine had an actual 3D hologram on its cover page, to the tune of millions of copies. The magazine featured a short description of how the cover images were produced (edited here for length).

How the Cover Was Made 1

“The bald eagle you see on our cover began as a tiny sculpture, produced by Eidetic Images, Inc., in Elmsford, New York. Eidetic, a subsidiary of the American Bank Note Company of New York City, used the eagle to construct the hologram.

“To mass-produce rainbow holograms after exposure by the laser, the hologram’s special emulsion, called photoresist, is developed, rendering the interference pattern as a series of ultrafine ridges. By electrolysis, particles of nickel are deposited on the ridges to make a mold. The nickel mold impresses the interference pattern into plastic, and a thin aluminum coating is applied. Functioning like a mirror, the coating reflects white-light waves through the interference pattern to create the changing image of the bald eagle model.

“This process was repeated almost 11 million times to create the holograms on this issue of National Geographic, the first major magazine to reproduce a hologram on its cover. It is best viewed in direct sunlight or light from a single artificial source. Though the sculptured eagle looks to its left, the cover hologram faces right for heraldic tradition.”

Producing the Eagle Hologram Cover

Back in 1983, when the magazine issue was being prepped and produced, National Geographic (along with American Bank Note Holographics), worked with several companies that had the ability to foil stamp the hologram on the covers. With a quantity of 11 million, it took many presses and locations involved in the process to make it happen. The majority of all of the covers were being run on 14 x 22 Kluge presses using a foil and hologram system designed by Terry Gallagher and his son, John Gallagher. They would later start a new company from this venture, Total Register, which installed hundreds of hologram registration systems through the 80s, 90s and 2000s. The holographic foil that included the holographic 3D image of the eagle was produced by Crown Roll Leaf and was supplied to those companies involved with foil stamping the covers by its distributor at the time – Old Dominion Foils.

One of those trade finishers involved in the project was Graphic Converting Inc. of Texas in Dallas, Texas. During that year, in 1983, Founder and Owner Robert Graham, Sr. (now deceased) was approached by American Bank Note Holographics (Terry Gallagher), National Geographic and Old Dominion Foils to help with the eagle hologram set to be included on the cover of the March 1984 National Geographic issue. PostPress talked with Robert’s son, Robert Jr., who was working at Graphic Converting at the time and recalls many of the ins and outs of gearing up for the mass production of the 11 million eagle hologram covers.

“When we were approached by American Bank Note, we recently had purchased the first Gietz FSA 720 to come to the US in 1982, and we were asked if American Bank Note Holographics could come look at the press to see if a hologram foil attachment could be built and installed,” remembered Graham. “I remember an electrical and a mechanical engineer came to Dallas to look at all the drawings of the press. In one month, American Bank Note designed both the electrical and mechanical equipment needed to add a hologram foil attachment to the press. This was the first hologram attachment installed on a sheet-fed reciprocating-style machine.”

Graphic Converting Inc. of Texas in Dallas became the hub for all sheets produced in Texas. The running timeline for production was a little behind. The company was told that National Geographic had never been late with its monthly editions so Graphic Converting had to do what it could to make the deadline.

“I remember being called to the front office by my father, Bob Graham, Sr., so we could meet with the printing director for National Geographic, who said he needed us to work as many hours as possible,” continued Graham. “He also asked what it would take to run two shifts on Super Bowl Sunday. We came up with a proposal: a TV and everything else for a party (except alcohol) plus a $300 bonus for each employee.” Graham remembers the last sheets leaving Texas the first week of March 1984, and the producers in Texas overall ran close to 2,000,000 covers.

Graham went on to mention that Terry Gallagher was the man who really invented everything it took to put 3-dimensional holograms in hot stamping foil, from the actual-size epoxy eagle model to creating the shim that embossed the image in the foil. The embossing diffracts the light to create the image, and the colors created are naturally occurring in white light. The foil used for the eagle hologram was silver automotive trim foil, which at the time was on a heavier mylar carrier, had more silver and was formulated with a sizing suitable for paper. On the Kluge foil units, the chain drives were replaced by stepping motors and a control console to make adjustments while running. This also was designed by Terry Gallagher and his son, John – part of the retrofit equipment they later would market to the foil stamping industry through Total Register.

Robert Graham, Jr. still is in the industry today, working for FSEA member TPC Printing & Packaging

(www.tpcpackaging.com), which produces folding cartons, rigid set-up boxes and trading cards in Chattanooga, Tennessee. “I always have dedicated myself to trying and learning new things while in this great industry. [I’m] proud to be a part of it for so long,” stated Graham.

Holograms Today

The mass production of holographic images has endured, and new advancements keep the technology on the cutting-edge and continuously improved for efficiency.

Besides the foil stamping of holographic images in register for both aesthetics and security applications, there are processes today that include custom holographic images within an entire layout for products, such as folding cartons, labels, magazine covers, posters and more. These applications include specialized holographic processes that then are laminated to board or paper and can be overprinted with a 4-color process to create amazing results. This use of holographic images is available through companies such as K Laser Technologies (www.klasergroup.com) and Hazen Paper (www.hazen.com). With this process, custom holograms can be included on a roll or sheet and then printed inline without registration of an image, providing opportunities to utilize holographic images within a design without the use of special registration equipment on a foil stamping press.

References

- “How our cover was made,” National Geographic, March 1984. Volume 165, Number 3.

The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame is a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting, preserving and celebrating the game of basketball. Each year, the organization recognizes a group of finalists of the sport’s elite – from players to coaches to referees – by formally enshrining that year’s class into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. A commemorative yearbook and enshrinement program is created to recognize the class and award recipients. Hazen worked with the Basketball Hall of Fame to take a graphic design and amplify it with holography.

The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame is a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting, preserving and celebrating the game of basketball. Each year, the organization recognizes a group of finalists of the sport’s elite – from players to coaches to referees – by formally enshrining that year’s class into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. A commemorative yearbook and enshrinement program is created to recognize the class and award recipients. Hazen worked with the Basketball Hall of Fame to take a graphic design and amplify it with holography.